Man as an Ecosystem

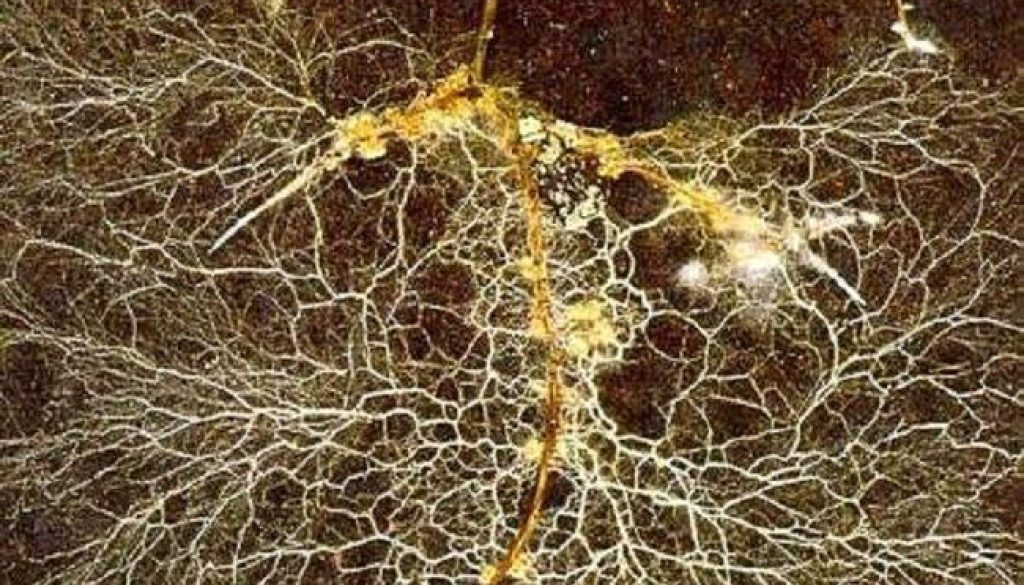

Humans are part of an ecosystem which we usually refer to as ‘reality’. This also allows us to say that, as an inseparable part of that system, we are also that system. In the sense that every part of a system, precisely by being inseparable, is also the whole system. Thich Nhat Hanh calls this ‘inter-being’. In Africa this is called ‘Ubuntu’, I am because you are, I am not because you are not. But in eco-physiology, this is nothing more than a given. An ecosystem is a system with a high degree of complexity that derives its resilience from the multiplicity and diversity of the interactions between its subsystems. We know from ecophysiology that an ecosystem with low complexity is much more vulnerable to major changes coming from outside the system. For example, a forest fire in a constructed forest for logging causes a long-term (decades) disappearance of the system. While a forest fire in a natural forest with its great variety of flora and fauna usually recovers within a few years. The same applies to fields with a monoculture that we often have to protect with all kinds of means against diseases and insect damage.

A human ecosystem is actually no different. If the interactions between people and between people and their environment are multiple and complex, then we see such societies flourish. Economists have studied the relationship between economic equality and the state of the national economy. This shows that countries with high wealth or income inequality tend to do worse economically than countries where income inequality is much less. Income or wealth inequality indicates a stratification of society that tends to intensify and drive different social groups further and further apart. Today’s social media add to this reinforcing effect. Social stratification leads to the tendency to favor one’s own group (subsystem) and stereotype the other groups. By doing so, we try to stabilize the status quo. This offers a certain stability of the situation in the short term, but the environment changes and the ‘stable system’ does not change with it, so that in the long run there is such a tension between the views within the subsystem and the environment (the encompassing system) that this will most likely lead to a collapse of the entire system.

From ecophysiology we have a nice example through the research of Prof. Marten Scheffer of Wageningen University. He studied the eutrophication of surface water in the Netherlands in the 1980s. By adding phosphate to the soap for the washing machine, an excess of phosphate came into our surface water. This caused an excess of algae blooms that made the water devoid of oxygen. The entire ecosystem died and only a green gunk remained. The government then banned the phosphate in washing machine soap, but although the phosphate disappeared, the algae did not and the eutrophication remained. Conclusion: the ecosystem had been destroyed by a strong external change (phosphate in surface water). By removing the cause, the system could not return to its former state. This is called a tipping point in the system. Only by making life difficult for the algae could the system eventually return to a healthy, diverse and thriving ecosystem.

Now the big question is: when do we approach such a tipping point? Because then we are approaching the dangerous moment when the larger ecosystem, of which we are a part, passes its tipping point and falls apart. This question is currently very topical in the face of climate change. Marten Scheffer’s research and that of many others in various fields show that a system that is approaching its tipping point shows a decrease in diversity and spatial homogeneity. The system shows gaps and sub-stratifications, as it were. For example, a grassland that suffers from drought will first show yellow patches among the green. After that, bald patches appear and only then does the grass disappear as a whole. This has been demonstrated in all kinds of ecosystems, but also in human societies. For example, we can see the polarization in the American political system as a harbinger of the collapse of that system. Something the trolls in St. Petersburg are eager to take advantage of.

In short, human society is a subsystem of the ecosystem we call Earth. If we are to survive, develop and ultimately transform as a system we will need to nurture our interdependence. That is, we must acknowledge our mutual differences and learn to integrate those differences through interactions, conversations and mutual respect. This is hard work and can be extremely frustrating and uncomfortable, but the alternative is the disintegration of our society and a very great loss of opportunity for our development.

Thich Nhat Hanh points out that what we need is not so much a new Buddha or Jesus, but a society of many enlightened people capable of acknowledging differences and facilitating their integration. This is a cry for a collective awakening.